As the 2024 Presidential campaigns ramp up, election lawfare is underway as well, with the political parties seeking to exploit ambiguities in voting rules or bend them in their favor, and we can only hope that its role will remain limited and not affect trust in the election. This article highlights the problematic nature of election lawfare, focusing on a controversial case from the 2020 Presidential election in Pennsylvania.

In 2020, in states with newly expanded mail-in voting processes where the parties battled in court over what would be permissible under the new rules and what would not be, with Pennsylvania a particularly active lawfare battleground. The case discussed and analyzed here resulted in extension of Pennsylvania’s originally mandated deadline for receipt of mail-in ballots, and likely had a material effect on the final vote tally.

The analysis, which is in part data-driven, calls into question the primary, stated rationale for extending the deadline, which was to ensure sufficient time for return of mail-in ballots for those who had been relatively late in requesting a mail-in ballot. It also offers a rough quantification of the net vote gain for Joe Biden arising from the extension.

While this number may have been material–possibly as many as 9,000 votes, it was far from enough to swing the election. Nonetheless, in combination with other perceived shortcomings of the process such as lax security around ballot drop boxes, the case contributed to a broader erosion of trust in the election outcome.

The Democrats’ legal challenge to the ballot return deadline

No-excuse mail-in voting was introduced into Pennsylvania by PA Act 77, which was legislated in 2019 with bipartisan support in the state legislature and the blessing of the Democrat governor (Tom Wolf). Although the Democrats in the state’s General Assembly in 2019 mostly opposed Act 77, the party had a change-of-heart by the summer of 2020. Conversely, at the national level during 2020, President Trump and other Republican leaders increasingly were expressing fears that no-excuse mail-in voting might facilitate election fraud.

Observations on voter turnout during the 2020 Primary in Pennsylvania might have helped motivate the Democrats’ embrace of mail-in voting. No-excuse mail-in ballots accounted for almost 40 percent of total votes in the 2020 Primary Election, underscoring the preference of many voters for the mail-in option. Although data on mail-in ballot shares by party are not publicly available, it is a reasonable presumption that Democrats in the Primary were more likely to vote by mail than Republicans, as turned out to be the case in the general election, and that this fact was known to strategists in each party. 1

Moreover, it seems that, because of the perception that liberalized vote-by-mail favored their party, Democrats were not content with a literal or narrow reading of Act 77. They adopted a strategy of lawfare to try and stretch the limits of mail-in voting as far as possible in order to maximize their perceived vote potential.

On July 10, 2020, the state Democratic Party, joined by some individual Democratic officials and candidates, filed a petition for review in the Commonwealth Court against Secretary of State Kathy Boockvar and all 67 county boards of elections. The petition requested declaratory and injunctive relief “to protect the franchise of absentee and mail-in voters.”2 Specifically, the plaintiffs asked the Court to rule in favor of a number of requested flexibilities, among which was to grant an exception to the deadline in Act 77 for receipt of mail-in ballots, such that any ballot postmarked by 8:00 p.m. on election day (November 3) and received by 5:00 p.m. on Tuesday, November 10 can be counted.

Technically, Boockvar was an opponent of the petitioners in the case. However, she herself was a Democrat, and on August 13, she filed a response that objected only to the requested seven-day extension of the received-by deadline, primarily on logistical grounds, proposing instead a three-day extension. Her response strongly concurred with the petitioners’ other requests.

On August 16, Boockvar filed an application requesting that the state’s Supreme Court exercise extraordinary jurisdiction over the petition for review; that is, take over for the intermediate appellate Commonwealth Court, in order that the resolution of these matters be expedited to preclude any disruption of the 2020 General Election. On August 19, the petitioners filed an answer to the Secretary’s application, indicating no objection to the Supreme Court exercising extraordinary jurisdiction. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court, where 5 of the 7 justices are Democrats, then took over the case.

The state Supreme Court ultimately agreed to an extension of the ballot receipt deadline by three days so that any ballot cast by 8 p.m. on Election Day, (Nov. 3, 2020) and received by 5 p.m. on Nov. 6 would be counted. The Court’s decision, which was based on majority opinion, was announced on September 17.

Review and critique of the petitioners’ arguments

The petitioners had argued that special circumstances arising from the Covid-19 pandemic justified a seven-day extension to the received-by deadline for mail-in ballots. Essentially, they contended that, due to the preference of many voters to stay away from polling places on account of the ongoing pandemic, the volume of mail-in ballot applications would likely overwhelm county resources, such that bottlenecks and delays in the processing of ballot applications and distribution of ballots would likely arise. Secondarily, they noted the potential for delays in the United States Postal Service (USPS) delivery system as an aggravating factor.

They argued that under the state constitution’s Free and Equal Elections Clause, which prohibits interference in or prevention of “the free exercise of the right to suffrage”, the state was obligated to take action to remedy the anticipated disruption to mail-in voting. As described in the Court’s written opinion:

Petitioner interprets this provision as forbidding the Boards from interfering with the right to vote by failing to act in a timely manner so as to allow electors to participate in the election through mail-in voting.

A key component of the petitioners’ argument was a claim that the kinds of obstacles to the timely processing of ballot applications that were encountered prior to the June 2nd Primary Election would recur and be even more severe. As summarized in the Court’s written opinion:

Petitioner avers that the difficulties encountered by Boards processing the ballot applications prior to the June Primary will only be exacerbated in the November General Election. It emphasizes the continued grip of the pandemic and a potential second wave of infections…. It highlights that the Secretary estimates that 3 million electors will seek mail-in or absentee ballots for the General Election in contrast to the 1.5 million votes cast by mail at the Primary.

However, the petitioners offered no substantive analysis to support this claim—only gripes about difficulties during the Primary and a poorly supported, inflated estimate of increased processing burden for the General Election.

During the Primary, many counties had indeed been inadequately prepared for the unexpectedly large volume of ballot applications they received, as this was the state’s first encounter with no-excuse mail-in voting. Thus, in some counties, most notably in Bucks and Delaware Counties, a significant number of ballots were mailed out too late for voters to return them by the deadline.

But clearly, county boards would have learned from their experiences in the Primary and taken action to shore up their capabilities in anticipation of needs for the General Election. The Court did not adequately consider what remedies might already have been implemented or what preparations were currently underway.

At least anecdotally, such ongoing efforts were substantive. A press report in late August contained the following assessment:3

Democratic leaders also contend they’ve remedied the issues that plagued them in the June primary when election officials were overwhelmed by a deluge of mail-in ballot requests during the coronavirus pandemic. It was the first time the state had conducted a mail-in election since a new law authorized the procedure last year.

For example, according to this report, Montgomery County had “used federal funds from the Cares Act to add eight staffers and more technology to help process the vote faster” since the Primary.

Another press report in early September included the following snippet:4

We were learning on the fly from February to June,’ says Jeff Greenburg, the director of elections in Mercer County until August, when he stepped down to work for The National Vote at Home Institute. ‘I really think Pennsylvania is in a better position now. … To me, we have a much better chance of succeeding because we now know what to do.’

Not only did the petitioners fail to back their claim that county boards remained inadequately prepared, but they overstated the anticipated increase in application processing volume. As evidence of increased burden, the petitioners had alluded to the gap between 1.5 million “votes cast by mail” in the Primary and 3 million anticipated applications for mail-in or absentee ballots for the General Election. This comparison, referenced in the Court’s written opinion, is misleading, as it is not apples-to-apples. The 3 million applications anticipated for the General Election is more appropriately measured against the total number of applications for mail-in or absentee ballots received for the Primary, which was 2 million.

Even that corrected numerical comparison, however, materially overstated the potential increase in processing burden, because much pre-processing of applications had already been completed. In fact, about 1.1 million individuals who had requested and been approved for a mail-in ballot in the Primary had signed up to be automatically sent a mail-in ballot for the upcoming general election, a highly pertinent fact missing from the discussion.

No further processing was required for the latter requests aside from the eventual automated printing and mailing of the ballots. Netting these out from the projected 3 million implies 1.9 million new applications for the General Election, not surpassing the 2 million processed for the Primary.

Review and critique of Boockvar’s arguments

Secretary Boockvar did not concur with the petitioners’ claim regarding the lack of preparedness of county boards, nor their request for a one-week extension. Instead, she advocated for a three-day extension based on the contention that those applying for mail-in ballots on or close to the statutory deadline for doing so, October 27, would face a high likelihood of missing the receive-by deadline for returned ballots if they chose to return them by mail.

The USPS delivery standards in effect at the time specified 2-5 day delivery for domestic First-Class Mail and 3-10 day delivery for domestic Marketing Mail. As described in the Court’s written opinion, “the USPS had advised that voters should mail their ballots no later than October 27 in order to meet the received-by deadline”. Boockvar argued that under these standards, a voter applying for a mail-in ballot on Oct. 27 would face a substantial risk of not meeting the November 3rd deadline:

…even if a county board were to process and mail a ballot the next day by First Class Mail on Wednesday, October 28th, according to the delivery standards of the USPS, the voter might not receive the ballot until five days later on Monday, November 2nd, resulting in the impossibility of returning the ballot by mail before Election Day, Tuesday, November 3rd…This mismatch [between the USPS’s delivery standards and the Election Code deadlines] creates a risk that ballots requested near the deadline under state law will not be returned by mail in time to be counted…

Further, Boockvar argued that mail delays associated with the pandemic would make the problem worse, selectively disadvantaging those who are applying for mail-in ballots shortly before the October 27 deadline and therefore necessitating a one-time extension of the received-by deadline:

The Secretary emphasizes that the remedy sought here is not the invalidation of the Election Code’s received-by deadline, but rather the grant of equitable relief to extend temporarily the deadline to address ‘mail-delivery delays during an on-going public health disaster’.

This argument, however, is specious. To begin with, it rests on the illusory notion that the application and received-by deadlines in Act 77 were originally flawed because of inconsistency with standard USPS delivery times.

The legislature could have opted for an earlier application deadline, whereby voters returning their ballot by postal mail would be more assured of meeting the received-by deadline. Instead, the legislature opted to provide more flexibility on application timing with the later application deadline.

Act 77 grants voters the choice to wait up to a week before Election Day to apply for a mail-in ballot, with the implicit, common sense understanding that voters will bear an increased risk of missing the received-by deadline the longer they wait to apply. To mitigate this risk, Act 77 also provides voters the option of hand delivering their mail-in ballots, including the option of applying for and submitting ballots in-person at an election office on the same day. To claim the deadlines were flawed is disingenuous.

Moreover, Boockvar’s argument presumes that voters have little or no agency — that those who apply close to the application deadline and consequently miss the receive-by deadline do so by fate — suggesting an obligation to provide such voters with flexibility on the receipt deadline when mail delays occur. However, voters can choose when to submit a ballot application. The possibility of pandemic- related mail delays should just change their calculation, motivating them to apply sooner rather than later.

Additionally, the argument fails to consider factors that would mitigate the effect of any pandemic-related mail delays. Drop boxes are one obvious mitigant. Surely, the availability of drop boxes for returning a mail-in ballot limits the risk that late applicants will miss the receive-by deadline. Another is to inform voters about the potential for mail delays and to encourage them to apply early, which was, in fact, the sensible advice being disseminated by the USPS at the time.

The Court decides

The Court’s written opinion indicates no awareness of any of these weaknesses in the arguments presented by the petitioners and Boockvar. The judges apparently were swayed by those arguments:

In light of these unprecedented numbers and the near-certain delays that will occur in Boards processing the mail-in applications, we conclude that the timeline built into the Election Code cannot be met by the USPS’s current delivery standards…The Legislature enacted an extremely condensed timeline, providing only seven days between the last date to request a mail-in ballot and the last day to return a completed ballot. While it may be feasible under normal conditions, it will unquestionably fail under the strain of COVID-19 and the 2020 Presidential Election, resulting in the disenfranchisement of voters…this Court can and should act to extend the received-by deadline for mail-in ballots to prevent the disenfranchisement of voters.

In short, the Court undertook to alter the deadline ensconced in plain print in the legislation, potentially skewing the vote outcome in favor of one party. The decision lacked factual support, and instead relied on an inaccurate and misleading estimate of processing volume and on nonsensical griping about a “condensed timeline.”

Quantifying the effect on the vote tally

The Court’s decision to grant a three-day extension to the ballot return deadline favored Biden due to the overwhelming ratio of Democrats relative to Republicans anticipated to vote by mail. It can also be seen as implicitly disfavoring those who were planning to vote at the polls, insofar as they were not extended any comparable flexibility, such as expanded hours at polling places or more than one day of in-person voting.

How many mail-in and non-overseas civilian absentee ballots did the Democrats manage to gain during the extended timeframe, net of ballots returned by Republicans? To address this question, we turn to a dataset from the Pennsylvania Department of State which has detailed information on each approved application for an absentee or mail-in ballot for the 2020 General Election. A link to the dataset, which is housed within the Department’s online Open Data Portal, was shared with the author in response to a “Right-to-Know Law” (RTKL) request.5

Individual data items include the date the application was received by the county in which the voter is registered. In addition, the data distinguish between traditional absentee ballots available to voters and the newly available, no-excuse mail-in ballots (henceforth to be referred to simply as absentee and mail-in, respectively) and further differentiate among types of traditional absentee ballots, such as military, overseas civilian, regular civilian, and so on.

The database also provides the date the ballot was received back by the county election office (the ballot return date). Non-return of a mail-in ballot that was sent to a requester is indicated by missing information in the return date field: if the ballot was not recorded as returned, then no return date is present.

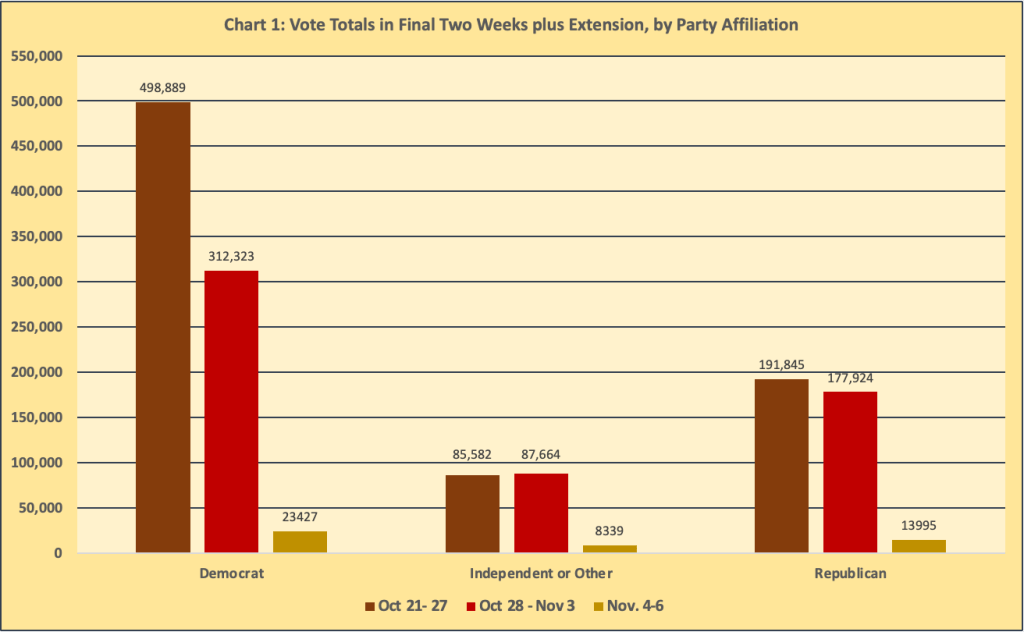

Chart 1 shows the counts of returned mail-in and non-overseas civilian absentee ballots received in the two weeks prior to and including November 3, the statutory deadline for returning these ballots, and the return counts for the three-day extension period granted by the Court. The counts are separated by party affiliation of the voters. During these three days, 9,432 more ballots were returned by Democrats compared to the number returned by Republicans.

While some of these ballots from Democrats might have been votes for Trump and some from Republicans might have been for Biden, there is no way to determine how many of each, and a best guess is to assume that such cross-party votes are few and mutually offsetting. Under the further assumption that Independent and other voters split equally between Trump and Biden, the net additional vote count for Biden is simply this difference between the returned ballot count of Democrat versus Republican-affiliated voters.

Does the extension seem justified in retrospect?

Chart 1 also indicates that the number of ballots returned from October 21 through November 3 swamps the number returned during the added three days. The number returned during the added days sums to 45,761, just 2.3 percent of the total number (1,987,793) returned on or after October 21.6 This small share seems inconsistent with the notion that pandemic-related mail delays would present a major obstacle to the timely return of mail-in ballots—the primary rationale put forth to justify the extension.

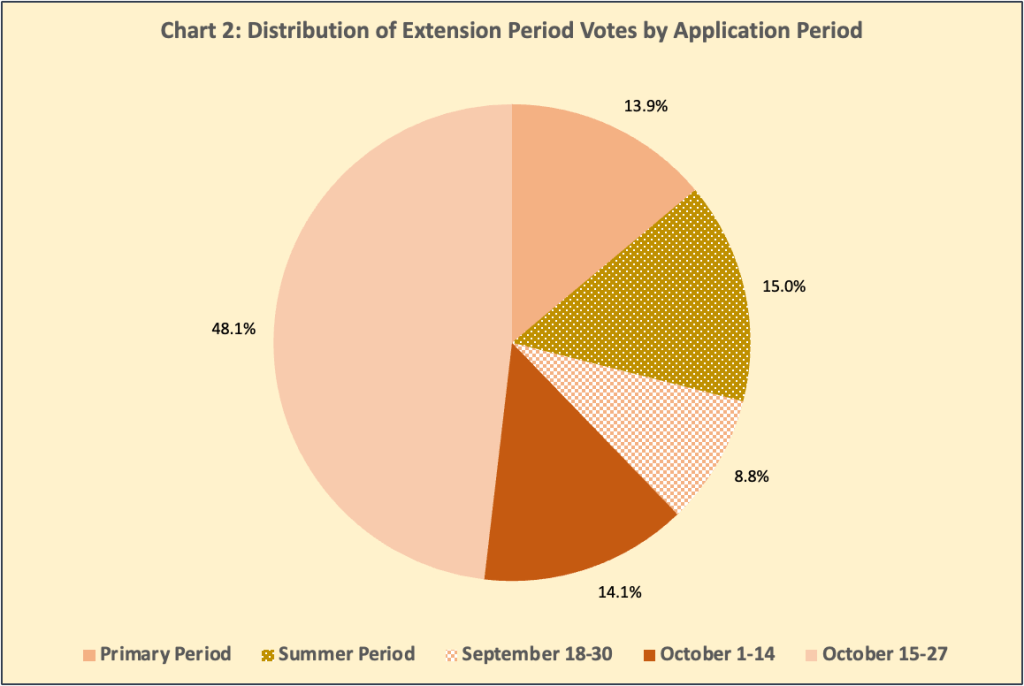

The three-day extension was motivated by a perception that those applying close to the application deadline would require this flexibility due to the potential for “systematic mail delays”. Chart 2 shows how ballots with November 4-6 return dates were distributed by application period. As seen in the chart, over half of the mail-in and non-overseas civilian absentee ballots with extension period (November 4-6) return dates were associated with applications filed prior to October 15; that is, applications filed well in advance of the deadline. Thus, most of those benefiting from extension of the deadline had not been late filers.

Another question worth asking is, how many of the ballots with application dates close to the October 27 application deadline would not have arrived in time had the extension not been granted? If there were many such ballots, then this could provide some ex-post justification for the Court’s decision.

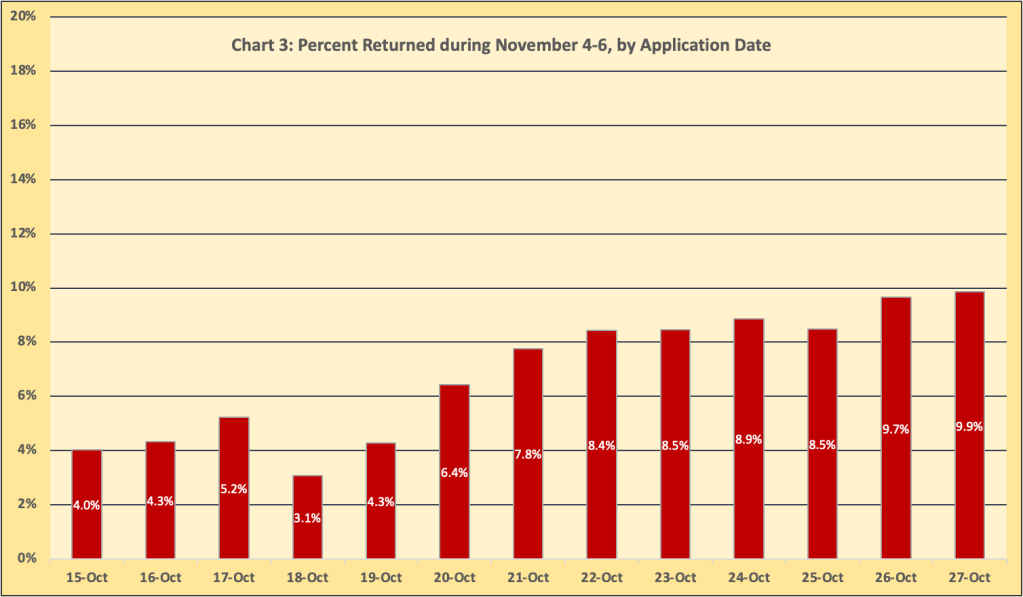

Chart 3 shows the percent returned during the November 4-6 extension period by date of application for each application date in the late October (October 15-27) application period. Not quite 10 percent of individuals applying within three days of the deadline had return dates on November 4-6, only a slightly higher percentage compared to individuals applying four to seven days before the deadline.

These outcomes seem inconsistent with the anticipated “systematic mail delays” put forth to justify the extension, and quite plausibly can be attributed instead to procrastination on the part of some individuals or to idiosyncratic factors affecting ballot return times. In retrospect, there seems to have been little justification for extending the deadline, especially as some individuals intending to vote in person may have missed their opportunity to vote due to idiosyncratic factors, and it seems unfair to have provided extra accommodation only for the mail-in voters.

Not all ballots with recorded return dates in November 4-6 are votes that would have been lost

If the Court had left the statutory deadline unchanged, then it seems quite plausible that some of the individuals whose votes came in during the added three days would have behaved differently, returning their ballots sooner.

In other words, voters’ behavior cannot be presumed independent of the stated deadline—voters would have adapted their behavior in response to changing the deadline. It is not possible, however, to determine how many voters with return dates on November 4-6 would have met the original deadline had it not been extended.

Likewise, the actions of those whose duty it is to collect and record ballots may have adapted to the extension of the deadline. In some cases, those responsible for collection may have left some ballots uncollected as of the close of business on November 3, knowing that there would be additional time for completing the task. Even if all ballots had been collected on the 3rd, some officials might have delayed opening and recording them until the next day, at which point they might be assigned a November 4 return date.7 The actual net gain to Biden due to the extension would depend on the total number of ballots incorrectly attributed to the extension period and how they divide up between Biden and Trump, which are also unknown quantities.

Enabling underperformance?

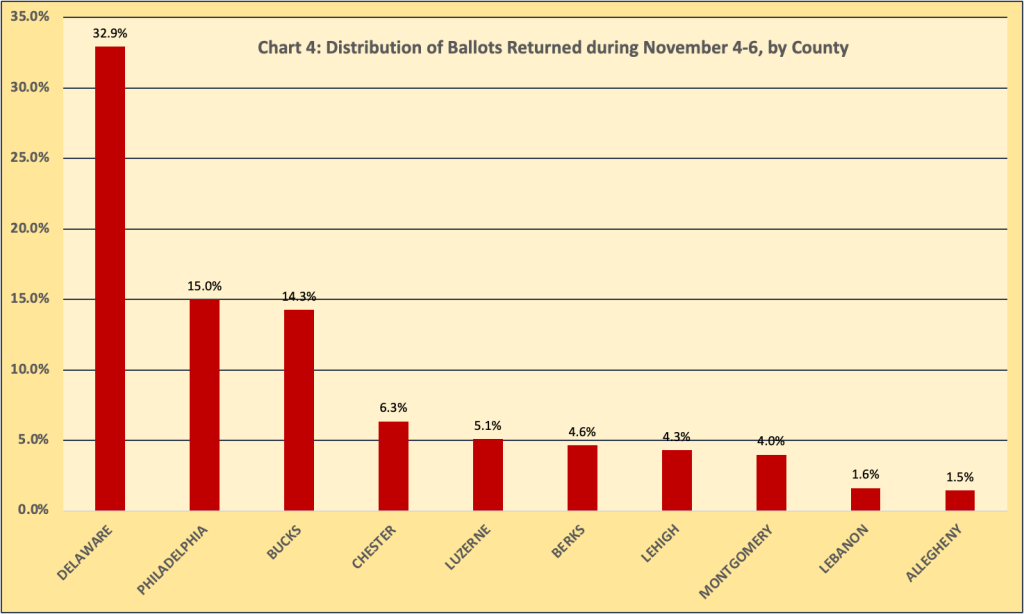

A far disproportionate share — nearly half — of the mail-in and non-overseas civilian absentee ballots with return dates on November 4-6 were from voters in just two counties, Bucks and Delaware. Chart 4 shows the distribution of ballots with November 4-6 return dates across the top 10 counties ranked by number of such ballots. Delaware County alone accounted for a third of all ballots returned during the three-day extension period. Bucks had about the same share of these ballots as much larger Philadelphia.8

These same counties, Bucks and Delaware, were notorious for having had especially severe delays in distributing mail-in ballots for the Primary in June. Uniquely among all Pennsylvania counties, these two had gone to their county courts to seek an extension to the ballot return deadline for the Primary. In fact, the experience of these two counties in the Primary was highlighted by proponents of the November extension as portending more systematic delays in the General Election. As described in the state Supreme Court’s written opinion regarding the November extension:9

…in Delaware County, thousands of ballots were ‘not mailed out until the night’ of the Primary, making timely return impossible… Bucks County apparently experienced similar delays. To remedy this situation, the Election Boards of Bucks and Delaware Counties sought relief in their county courts… the Courts of Common Pleas of Bucks and Delaware Counties extended the deadline for the return of mail-in ballots for seven days, so long as the ballot was postmarked by the date of the Primary.

Hence, one might reasonably conclude that the primary accomplishment of the Supreme Court’s granting the three-day extension was to relieve these two counties from responsibility for making needed improvements to their ballot distribution and collection processes. Surely, in retrospect, this is insufficient justification for the Court’s decision.

Concluding remarks

The troubling nature of election lawfare is exemplified by a particular case from the 2020 Presidential election in Pennsylvania in which the Democrats convinced the state’s Supreme Court to extend the deadline for receipt of mail-in ballots. In short, the Court undertook to alter the deadline ensconced in plain print in the legislation, potentially skewing the vote outcome in favor of one party.

The decision lacked factual support. Rather, the judges (the majority of whom were Democrats) were swayed by inaccurate and misleading information that was presented to them, and by a nonsensical, emotionally driven argument about a “condensed timeline” for mail-in voters arriving late to the game.

The Court’s decision was wrongheaded, because of the weak reasoning brought to bear. Overriding the explicit requirement of the legislation without adequate justification amounted to judicial overreach.

A bit of irony is evident here, considering the lawfare conducted in 2020 by the Democrats against the Green Party in Pennsylvania. A Green Party official chose to fax (as opposed to hand deliver or mail) a candidate affidavit, which was technically a violation of candidacy requirements. This minimal infraction, during the state’s Covid lockdown when office hours were limited and direct contact between persons discouraged, could have merited forbearance, but the Democrats succeeded in expelling the Green Party candidate from the ballot. Whereas the Democrats would grant no leeway to the Green Party, they self-servingly pursued a far greater degree of forbearance regarding the statutory ballot receipt deadline, based on flimsy justifications using the pandemic as a pretext.10

Analysis of mail-in voting data from this election casts further doubt on the notion that extending the deadline was necessary to ensure sufficient time for return of mail-in ballots for those who had been relatively late in requesting a mail-in ballot. In particular, the data show that most of the ballots that arrived during the three-day extension period were not from late applicants.

The extension of the ballot receipt deadline yielded a material net vote gain for Joe Biden resulting from the extension–possibly as many as 9,000 votes–and alongside the Green Party’s expulsion and other factors contributed to a broader lack of trust in the election outcome. Let us hope that in 2024, experiences such as this, where lawfare is used as a means of acquiring an unfair advantage, are not repeated.

Footnotes

- In the 2020 Presidential Election, 57.7 percent of votes cast for Biden, but only 17.6 percent of votes cast for Trump, were by mail-in or absentee ballot, according to the state’s official election results. ↩︎

- The case history discussion is drawn from the Opinion recorded by Justice Baer for the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s September 17, 2020, decision on this case. ↩︎

- Roarty, Alex, and David Catanese. August 27, 2020. “Despite uncertainty, Democrats bet big on mail voting in Pennsylvania.” McClatchyDC.com. Link. ↩︎

- Bryant, Christa Case. September 4, 2020. “Why Pennsylvania is ground zero for mail-in voting debate.” The Christian Science Monitor. Link ↩︎

- The link was provided in a RTKL response letter dated March 25, 2021; however, the dataset itself might already have been publicly available. The version currently accessible through this link may incorporate some updates relative to the dataset used here. ↩︎

- Broken out by party affiliation, the shares received during November 4-6 were 1.9, 3.5, and 2.7 percent for Democrats, Independents or other, and Republicans, respectively. ↩︎

- In fact, it is almost certain that some ballots recorded as returned on the 4th actually were returned on the 3rd. For five outlier counties, the data show zero or near zero ballots returned on the 3rd but a far larger number on the 4th, which is not credible. These five outlier counties and their ballot counts for November 3rd compared with the 4th are: Clinton (6 versus 169); Luzerne (5 vs. 2,076); Sullivan (1 vs. 33); Lebanon (0 vs. 729); and Mifflin (0 vs. 513). In the rest of the state, more than three times as many ballots had a return date of the 3rd relative to the 4th. ↩︎

- Philadelphia had about 2⅓ times as many registered voters as Bucks County. Montgomery had less than a third the number of ballots with November 4-6 return dates relative to Bucks, despite having about 40 percent more registered voters. Also note that the shares for Luzerne and Lebanon shown in the chart are inflated for the reason described in the previous footnote – zero or near-zero ballots with November 3 reported return date. ↩︎

- See pages 21-22 the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s September 17, 2020, decision. ↩︎

- For a wider ranging discussion of lawfare cases initiated by Democratic Party activists during the 2020 election around the nation, see chapter two of Fund, John, and Hans von Spakovsky. 2021. Our Broken Elections: How the Left Changed the Way You Vote. New York: Encounter Books. ↩︎

Leave a comment